In my previous entries, I have referred to government bonds and their so-called risk-free nature. I have even promised to write more about them!

In this entry, I am going to discuss them in general terms, the risks associated in investing in them (yes, there are risks!) and several ways to invest in them. So let’s get into it.

Disclaimer

I am not authorised to give financial advice. All my writing is purely my opinion, based on my own research, thinking and experience both working in the industry and investing my own money. However, I have never invested in government bonds!

What is a (government) bond?

A bond is a (metaphorical) piece of paper which states that the issuer has borrowed some amount of money from the bond investor/lender. The issuer is then obliged to make regular interest payments to the investor, colloquially known as coupons. When the bond reaches its maturity date, the loan expires, and the borrower repays the original amount borrowed back to the lender.

A government bond is simply one that is issued by the government of a country. In the UK, it is issued by the Debt Management Office on behalf of HM Treasury. Why do they need to borrow money from investors? Well – they have a tendency to spend more than they earn. Loads more. But that’s for another story.

Here is an example of an actual government bond – in this case it is Uncle Sam. In the good old days, you had to tear off the coupon from the paper bond, mail it to the US Treasury so they knew where to mail the cheque! Thanks to advances in technology, it is all now done electronically.

Figure 1 – an example of a US government bond

Look at the picture of the bond in more detail (you might have to squint a bit – I got it off the internet for free) and you will see the main features of a typical bond.

Notional amount – the original amount borrowed, in this case $100

Coupon – the bond title claims it is a 4.25% bond. The individual coupons show $2.12 interest payment every April, and $2.13 every October, totalling $4.25 per year.

Maturity – the dates ‘1933-1938’ implies that the US Treasury had borrowed $100 in 1933 for a period of 5 years.

Other types of bonds

The example in figure 1 is one of the most basic and common type of government bond. There are many different types of bonds you can find in the market. I will not go through them in detail here, but other bonds may have variations in their features as in the below list (though this list is not exhaustive)

Issuer – e.g. corporations, local government agencies

Coupon type – zero coupon, variable coupon, step-up/step-down coupon

Maturity – callable (the issuer can choose to repay the loan or not on certain pre-set dates), perpetual (have no maturity date so the issuer simply continues to pay the regular coupon forever)

Convertibility – may be converted into shares when certain features are met

The “Risk-Free” Nature of Government Bonds

So now that you know what a government bond is, let us have a look into it a little bit more.

Government bonds are often described by financial advisors as either ‘risk-free’ or as investments having ‘lower risk’ than shares. You will often hear people say that you should ‘diversify your portfolio by having government bonds to lower your risk’ – or comments along similar lines.

So, are government bonds risk free? The answer is both yes and no. It depends on what kind of risk you are considering.

Let us now pretend that the US Treasury bond in figure 1 was actually a UK government bond, denominated in poundsterling with a notional of £100, a yearly interest of 4.25%, paid every year (instead of every 6 months), was issued in March 2023, and would mature in March 2028. Let us also assume that you had purchased the bond upon its issuance.

The chart below (not to scale) shows you the cashflows over the next 5 years. You will have ‘paid out’ £100 to buy the bond and receive the coupons every 6 months. In March 2028, you will have been paid back the £100 by the UK government, along with the last interest payment.

Figure 2 – cashflows associated with bond from figure 1 (with £ as currency and annual coupon payment instead)

The ‘Yes’ Part of the Answer

The ‘risk-free’ description of government bonds come from the assumption that the UK government has no chance of defaulting on an obligation in its own currency. This is because in an extreme scenario it can print more pound sterling in order to make the coupon and notional payments of its bonds.

If, for whatever reason, HM Treasury runs out of cash in March 2028 and nobody else wants to lend them more money (yes, they do borrow more money to repay old loans – officially known as refinancing), they can print more pound sterling and pay you the £104.25.

For all intents and purposes, the cashflows are guaranteed. You will receive those coupons and the government will pay you the original loan back in 5 years’ time if you hold the bond to maturity.

However….

The ‘No’ Part of the Answer

Those of you who have read Blog 2 will have remembered that in 2022, government bonds lost its value. The gilts index fund lost a staggering twenty seven percent of its value over the year! Twenty seven percent! That is nearly one third! You are allowed to wonder what is so ‘risk-free’ about government bonds.

The key point is that government bonds are risk-free only when you hold them to maturity. By holding them to maturity, you will have locked in a fixed interest rate and the cash flows are guaranteed.

If you need to sell them before maturity day, you might have to sell at a loss (or a profit if you’re lucky). Government bonds fall in value when interest rates go up, as they did in 2022 across the world. Conversely, they can rise in value when interest rates go down.

Price Changes in Government Bonds

This next section may sound rather technical, but what I hope to show you – in the least technical way possible – is how government bonds change in value. So please bear with me.

Firstly, always remember that when interest rates rise, bond prices fall. Conversely, when interest rates fall, bond prices rise.

Let us use the hypothetical UK government bond (based on figure 1) as an example. When bonds are issued, the coupons usually are set at the prevailing interest rates for the borrower for the relevant maturity date. In this case, for every £100 borrowed by the UK government, the total coupon payment is £4.25 per year. This is also known as the yield of the bonds, of 4.25%.

Scenario 1 – rise in interest rates

Say you had invested in £100 of the hypothetical bond at a yield of 4.25% and that the following day, the interest rate at which the UK government would have to pay to borrow some money suddenly rose to 6%. What happens to the value of your bond? It falls in value.

To help explain this, imagine your cousin is now interested in lending money to the UK government. They have two choices.

They could buy a newly issued bond (if available) directly from the UK government, paying £100 and earning £6 a year.

Alternatively, if you are interested in selling your bond, they could buy it from you instead. However, the bond you hold only pays £4.25 per year. To ensure that they earn the same rate of 6% a year, they should only be willing to pay you £92.63, instead of the £100 notional for the bond that you own.

If your cousin buys your bond from you, they will still receive £4.25 in coupon annually and if they hold it to maturity, they will also receive the full £100 from the UK government. This ensures that they obtain a yield of 6% on their investment of £92.63.

The cashflow profile looks like this instead (again, not to scale)

Figure 3 – cashflows for the same bond after rates have gone up to 6%

Scenario 2 – fall in interest rates

Similarly, the opposite is also true. If the interest rate that the government pays to borrow money at falls to 2%, the bond price for £100 of notional would rise to £110.61.

In order to receive £4.25 a year in coupons and to be repaid the £100 notional at maturity from the UK government, your cousin would be willing to pay you £110.61.

For those of you who are interested, I will show how to obtain these prices in Appendix 1.

Why Invest in Government Bonds

I must admit that I have never purchased a government bond nor a fund that invests purely in government bonds for my personal investment. There are a couple of reasons for that. I am in my early forties, and I have been focused mainly on capital growth for the long term – see Blog 2.

Furthermore, since I started having any money to invest, returns from government bonds have been diabolically low, or even negative in some cases. Instead of providing risk-free returns, they have provided returns-free risk!

However, I do think they have a place in some people’s portfolio and to my mind, there are two good reasons to hold government bonds:

If you have an outgoing commitment on a fixed date in the future, and you have the money now, you might want to purchase a government bond maturing shortly before the commitment date. This way, you still earn some returns whilst not having to bear any short-term fall in value associated with investing in stocks.

2. To have a portion of your portfolio earning a fixed amount of return without any potential loss of the initial investment. You need to consider two things here:

What proportion of your investment you want to be ‘risk-free.’ I have not thought of what my own answer is to this question.

What the minimum level of return is that you wish to obtain through government bonds. At the time of writing in March 2023, the 5-year return on UK government bonds is just over 3% per year. I personally would only consider investing a significant portion of my investment in bonds if the return is at least 5%.

I have said it earlier and I will say this again. Only buy government bonds if you plan to hold them to maturity. This is the only way to guarantee that your investment is ‘risk-free’. Otherwise, the short-term volatility in the value of the bonds is not worth the potential for long term returns.

Ways to Purchase Government Bonds

To my knowledge, there are two ways of doing so. Firstly, through investment funds. An example is given in Blog 2. Secondly, you purchase the government bond directly through your broker.

By the way, have I mentioned that you should only buy government bonds if you hold them to maturity?

For this very reason, I do not recommend buying funds that invest solely in government bonds. Why? Because you are inadvertently taking a view on the direction of interest rates. A fund investing in gilts does not have a maturity date and will always replenish its holdings in bonds as older positions mature.

Using the gilts fund from Blog 2 as an example, here is the maturity profile of the bonds held by the fund.

Figure 4 – distribution of holdings of Vanguard UK Government Bond Index Fund by maturity

Just over 27% of the value of the fund is held in bonds that will mature in the next 5 years – see the top two bars in the chart. As they mature one by one and the UK government pays the loan back, the fund manager will use the proceeds to reinvest in new bonds being issued.

The investment fund does not have a maturity date and thus you cannot lock in a fixed level of returns associated with holding a government bond to maturity.

Conclusion

I do believe that government bonds have a place in some people’s investment portfolio, especially now that interest rates are starting to rise again. You should consider what proportion of your portfolio should be in this ‘risk-free’ asset and what the minimum level of returns is that you require from the bonds.

Make sure that you buy the government bonds directly, rather than an investment fund that holds only government bonds. Then hold the bonds to maturity. This way, you will lock in a fixed rate of returns and guarantee the ‘risk-free’ nature of the instrument.

Do not expect to make great returns from this instrument. And no, the short-term volatility is never worth the potential (or lack thereof) of potential long-term returns.

Appendix 1 – Bond Pricing

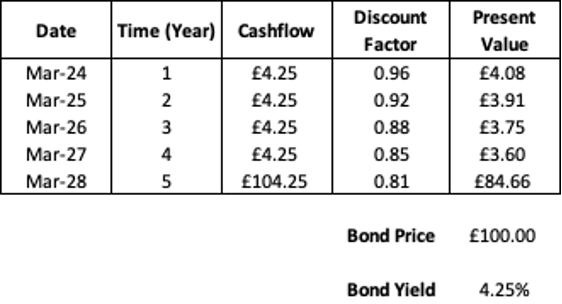

Now this section is technical. Determining the price of a bond involves a technique known as discounted cash flow. The cashflow of a bond is known based on its coupon levels and maturity date. What you need next is the discount rate or yield, in order to discount the cashflows to get their Present Value. Yield is another term for the interest rate that the borrower needs to pay now to borrow that money.

Figure 5 – discounted cashflow of modified bond from figure 1 when priced at £100 per £100 of notional

The Discount Factor in each row is calculated as 1 / [ (1 + yield) ^ time ]. That is one divided by {(1 + yield) to the power of time}.

The Present Value of each cashflow is the cashflow multiplied by the discount factor in each row.

The sum of the present value of each cashflow is the price of the bond.

The below table shows the discounted cashflows of the bond when interest rates/yield have gone up to 6%

Figure 6 – cashflows of modified bond from figure 1 after yield has risen to 6%

Set up the table above in a spreadsheet for yourself and see if you can get the price of £110.71 for each £100 notional when the bond yield is 2%. It is not that hard to do.

Appendix 2 – are all government bonds truly ‘risk-free’?

If you got this far, I would like to highlight another technical point. A government bond is risk-free if and only if the government has full sovereign rights over the currency in which the bond is issued. What do I mean by this?

A UK government bond issued in pound sterling is risk-free because the UK government, along with the Bank of England, can increase the supply of the pounds indefinitely (OK – maybe not indefinitely) but they can print a lot more pounds to pay you back should they need to.

The same is true for US government bonds issued in US Dollars and Japanese government bonds issued in Japanese Yen.

However, I would question whether government bonds issued by Eurozone countries are risk-free. German government bonds are treated by the financial markets as the benchmark risk-free bonds denominated in Euros. However, the German government does not have full control over the Euros and the European Central Bank. The same is true for government bonds issued by the Spanish, Italian or Greek governments (amongst others).